Abstract

What was that obscure Git command again? A quick Google search should do the trick, but was it the first, second, or third link? We all wish we had a sidekick who remembers all the relevant information at all times. Problem is, we will annoy people if we ask the same question multiple times. On the other hand, we can become annoyed with the overwhelming number of search results that are mostly irrelevant to us. What if there was a better way to manage knowledge and you, a software engineer, had all the skills to make it happen? Meet the Second Brain, a note-taking technique that not only will improve your Time To Answer, but also has a potential to improve your engineering skills and make you a happier person.

What is it?

A Second Brain is our personal repository of relevant knowledge, how-to guides, code snippets, and other useful resources, gathered in the form of notes. However, actually building such repository may be a really tough task — at least it was for me, because I didn’t have any established way of taking notes before.

The book “Building a Second Brain”1 by Tiago Forte has an abundance of useful techniques and guidelines to capture, organize, distill, and express2 the knowledge we gather in our note-taking journey. This article explores those techniques through the lens of a software engineer.

Quick start

Starting with your Second Brain should be like starting a new software project: do just enough upfront work to get you started, but try to make decisions that will speed you up in the future.

You could start a new software project with only deciding on a language, but the work will go much more smoothly if you have a Continuous Delivery pipeline in place and have a testing library set up with easy access through your IDE. You are the user of the development process, so create the best user experience you can.

The two important factors contributing to a good note-taking experience are note capturing and ease of note organization.3 It is important not to compromise on either, because otherwise you will just stop taking notes altogether.

There will be no notes if you are discouraged to take them in the first place, so it’s crucial to have a setup for near-automatic note recording. Think about the simplest app for jotting down your messy thoughts. That will be your go-to.

You also have to think about your ideal setup for organizing text files. As a software engineer, you already have a huge advantage. Whether it’s VSCode, Neovim, or Emacs, there are plugins that will help you connect your notes. If you don’t already have your preferred application, Obsidian may be a good place to start.

Organizing your notes matters for the same reasons we organize our code. Well-factored code is easier to navigate, easier to grasp, and easier to use. It is especially important when taking notes, because good notes save our time by being a more convenient source of relevant information than, for example, search engines.

You can read about my approach in My setup section.

Connecting ideas

One feature I find particularly useful when building a Second Brain is the ability to make and visualize connections between ideas.

For example, in Dave Airey’s book “Logo Design Love,” he found in his professional work that contacting decision makers directly when getting feedback about the logo design causes less trouble and disappointment than contacting a middleman.4 It is the same problem Extreme Programming mentions: real customer involvement.5

It feels obvious and natural that there is a connection between these two books, but if you read them one or two years apart, it is almost impossible to make such connections without a robust set of notes. Because of the recency bias,6 we tend to better recall the information we acquired recently. The Second Brain can mitigate that, opening new possibilities of research.

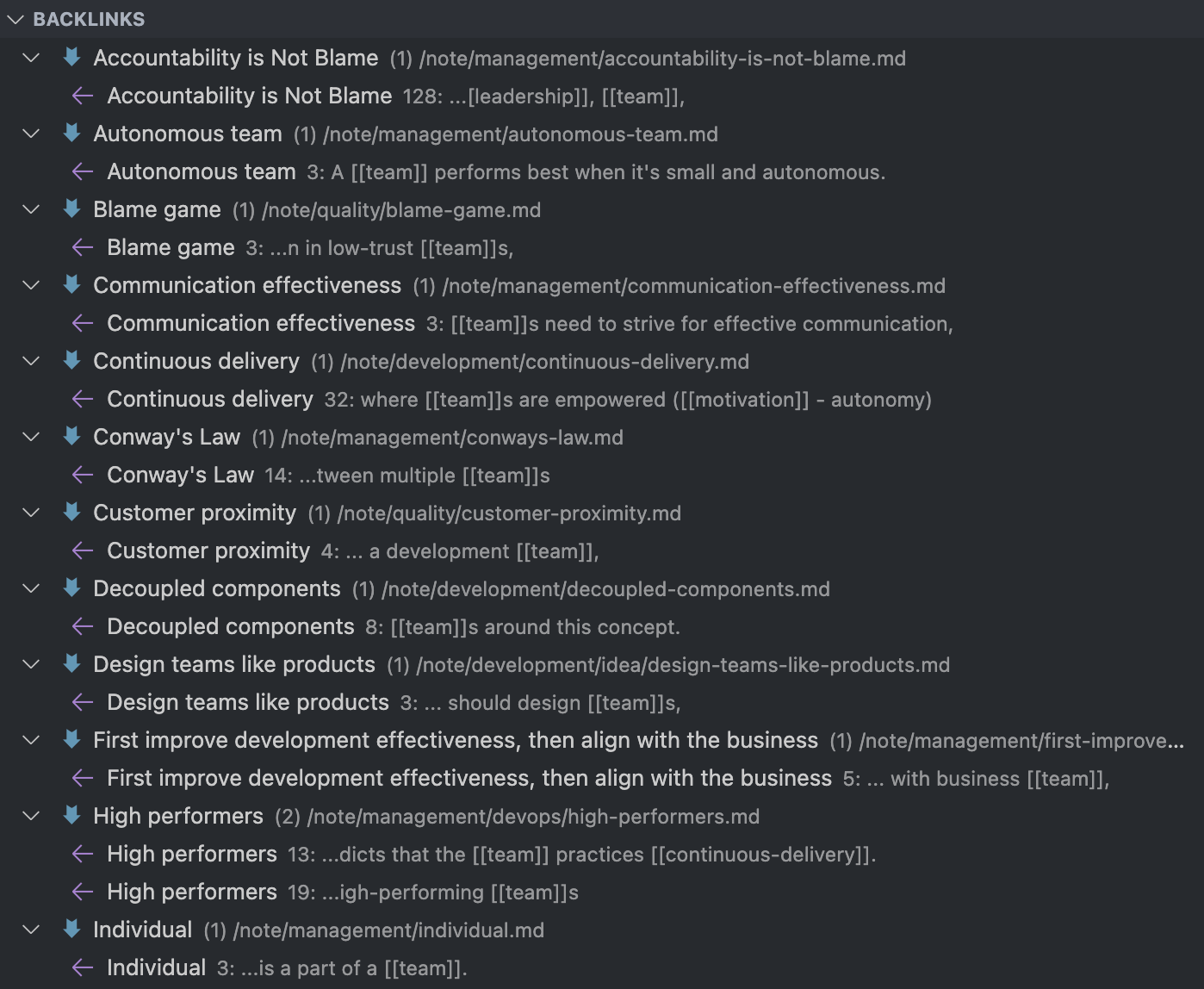

We can see the connections both through links and backlinks, described in detail in this section, as well as on a graph. Those options make for a great exploratory tool, especially when we want to freely gather relevant information, but we don’t want to limit ourselves to one topic.

Go to definition or references

There are many tools that can help us navigate

through our notes in a similar way that an IDE

enables us to quickly navigate our code.

When using Foam,

we can use WikiLinks to link our notes.

It’s a common linking implementation,

which can also be found in other note-taking applications,

like Obsidian, Roam Research,

Logseq, or MediaWiki

from which this linking style originated.

Such links are usually file names of another notes

without the .md extension,

wrapped in double square brackets:

1# A note

2

3This note links to [[another-note]].

One way to navigate through the connected ideas is simply going through the links we made inside a note. In Foam, it is simply done by putting a cursor on a WikiLink, and pressing Go to definition shortcut. We can also navigate to references from the Backlinks panel, similar to what we do in code.

Visual navigation

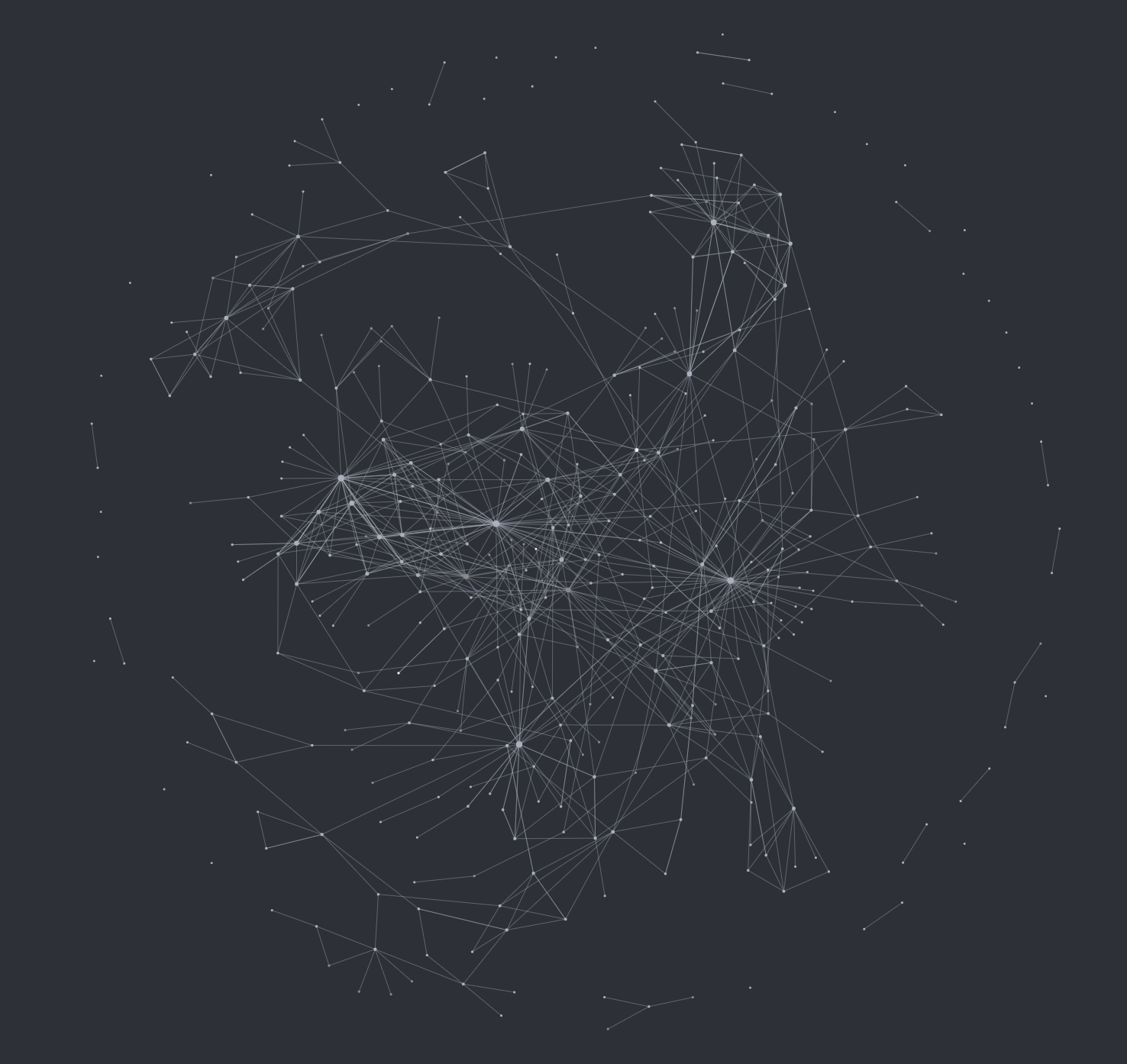

Another great feature, which most applications implement is a graph view of your notes. Each note is represented by a node, and each link as an edge. You can explore your graph, see how many links are between the ideas, and discover new, surprising analogs, which would be much harder to explore otherwise.

You can zoom out and see a general overview to identify the most profound ideas, spanning the entirety of your notes.

You can also zoom in to see the individual notes and connections between them.

Note-taking as communication practice

We all need to communicate with other people every day, everywhere. Clearly expressing our thoughts is very hard, yet it’s one of the most important skills in life. I observed that note-taking helped me make my explanations more understandable, my arguments more substantial, and simply improve my ability to retrieve relevant information on the spot.

We want to aim at expressing our thoughts to other people regularly, in order to gather feedback on the quality of our notes and communication. We need to gather what we already have and actually produce the first version of an important argument, article, speech, or presentation.7 We can then gather feedback on that version and iterate, so that the next version is more concise, easier to understand, and resonates better with the audience.

Furthermore, when we write our notes for our future selves, we have to think about forgetting the context with time. A reader of a text has a fundamentally different thought process than the writer.8 Thus, we have to place ourselves in the role of the reader so that we can make a useful note for the future.

Note-taking as programming practice

One thing every software engineer needs to do is to practice.9 It is especially true for hard or common things we all have to do every day. Refactoring code, clearly expressing our ideas, or giving them a proper name. It turns out that note-taking can help us with a lot of those things.

When I read a book or listen to a conference talk, I make a note of each idea that sticks with me. That means, I have to understand it well enough to verbalize it into a comprehensible text. I also need to keep in mind that I write it for my future self, so it becomes a bit like explaining an idea to your colleague.

When I have that idea in writing, I have to come up with a clear, short name, which can be easily searched for, and will link nicely with other ideas. In short—design my notes for my future self. However, just like with every design, be it in software or graphic design, we rarely come up with the best idea the first time. Therefore, we need to refactor our notes.

Refactoring notes

Refactoring our notes should have a similar goal as refactoring code.

Refactoring is the process of changing a software system in a way that does not alter the external behavior of the code yet improves its internal structure.10

The external behavior in code can be an equivalent to knowledge or data in our notes. We can’t alter the facts here, that part is for the research phase.

We’ve got an abundance of well-documented refactoring techniques, so let’s explore how we can apply them to improve our notes.

The first obvious refactoring is renaming: we’ve assigned a name to our note, but the more details we add to it, the more it turns out to be wrong. Then we can simply change the name of our note. We can also add some keywords or labels at the beginning or end of our note to make it easier to search.

From my experience, the best way to ensure good searchability is to put a new label or rename the note whenever we don’t find the right one on our first search.

Another way we can make our notes easier to read is to extract a portion of our note to a new one. With extract method refactoring, we want to achieve a consistent level of abstraction and detail in our methods. We want our notes to be consistent in their specificity, because there will be times where we only need a general overview of the subject, and reading through countless paragraphs of detailed explanations will only slow us down.

Optimize for learning

To take great notes, as well as develop great software, we need to become experts in learning. Every person has their own optimal way of learning, but fortunately, practicing note-taking can help us explore our own preferences for quick and effective learning.

There are, however, some universal characteristics of a good learning process. In “Modern Software Engineering,” Dave Farley wrote that to become experts at learning, we need:11

- Iteration

- Feedback

- Incrementalism

- Experimentation

- Empiricism

When taking notes, we can practice most of those points. We can iterate on our notes, continuously making them more concise and more useful for us (distilling them),12 based on the feedback of how easy they were to retrieve and understand, some time after writing them. We incrementally add new knowledge to our repository, doing more detailed research for our problem at hand.

Moving on

Let’s say you have some unorganized, “legacy” notes spread across different directories or services. It would be a good idea to have them organized and properly linked, but it would require a lot of time and effort that you probably don’t have.

Just like with technical debt in software, unorganized notes are only bad if we have to deal with them. So my advice would be to gather all of the legacy notes into one place, for example, a directory named “archive” and just move on with your current notes.

The same goes for the projects you’ve already finished. Take a glance if some notes would be useful for some future projects and organize those, but put all the rest in an archive. Move on with your projects, work, knowledge, and life.

Moving inactive notes to archive will make your workspace cleaner, which in turn will help you focus on your present goals instead of going through a bunch of old notes.13

Remember, you can always search through all your notes and if something interesting pops up in your archived ones, you can always move or copy them to your working directory.

Happiness

Externalizing our thoughts through writing has a lot of benefits, both in psychological and even physical health.14 It can reduce stress and make us more present in our daily life. Think about different situations when you just couldn’t get rid of those excruciating thoughts:

I have to remember to take out the laundry before I go to work. Oh, and my friend has birthday today. Hmm… I think I’ve just found a solution to a bug I’ve investigated yesterday, so I have to remember that as well.

You get the picture.

Instead, just set a timer for an hour before the laundry is done, put your friend’s birthday into a calendar, and a solution to a bug into your note-taking app. You will immediately feel relieved. Over time your brain will trust the system more and more and you will become less stressed, at least when you will have to remember something.

My setup

Although my setup is in VSCode, which I use every day for development anyway, unless you have a similar situation, I’d advise you to start with Obsidian, which will provide a wonderful note-taking experience out of the box.

My ideal setup for organizing text files has to be version controlled with Git, use Markdown format, have search with regex, and support Vim keybindings. That’s why I’ve set it up like any other Git repository, and I organize it in VSCode with Foam plugin. I’ve written a Github Action that automatically converts a Github issue to a Markdown file in an “inbox” directory.

Footnotes

-

T. Forte, Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organise Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential. Profile, 2022.

-

The CODE strategy stands for: capture, organize, distill, and express — the four note-taking stages. Described in detail in “Building a Second Brain.” (pp. 43–50).

-

T. Forte, Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organise Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential. Profile, 2022. (pp. 43–50).

-

D. Airey, Logo Design Love: A Guide to Creating Iconic Brand Identities, 2nd ed. New Riders, 2015. (p. 111).

-

K. Beck and C. Andres, Extreme Programming Explained: Embrace Change, 2nd ed. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2004. (pp. 61–62).

-

Wikipedia, “Recency bias”, 2022. [Online source] (accessed Mar 2, 2023).

-

T. Forte, Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organise Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential. Profile, 2022. (pp. 180–182).

-

University of Chicago. The Craft of Writing Effectively, (Jun. 26, 2014). [Online Video]. (accessed: Dec. 14, 2022). (7:26–10:22).

-

R. C. Martin, The Clean Coder: A Code of Conduct for Professional Programmers. Prentice Hall, 2011. (Chapter 6).

-

M. Fowler, Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code, 2nd ed. Addison-Wesley, 2019. (Preface, p. xiv).

-

D. Farley, Modern Software Engineering: Doing What Works to Build Better Software Faster. Addison-Wesley, 2022. (p. 4, 36)

-

T. Forte, Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organise Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential. Profile, 2022. (pp. 120–126).

-

T. Forte, Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organise Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential. Profile, 2022. (pp. 102–108).

-

T. Forte, Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organise Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential. Profile, 2022. (p. 77).